Committed to the present & the future!

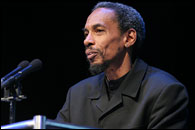

1. Meeting Roi Kwabena

I first met Roi Kwabena in late September and early October 2002 at the launch of Black History Month in Birmingham,UK, and was privileged to witness one of his performances. Roi performed some poetry to the accompaniment of some drums he played himself.

As I asked him where he got his inspiration from, he replied "It wasn't me playing there, you know !", with that characteristic twinkle in his eye. When I finally got to read his poetry, I understood the meaning of that answer : Roi is a bit like Peter Tosh's "mystic man", a "man of the past, living in the present and stepping in the future". Indeed, the Caribbean oral tradition looms large in Roi's work, but he remains totally committed to the present and the future.

Thus, Roi's poetry addresses Caribbean, pan-Caribbean and global issues while remaining steeped in that tradition. All this appears in the interview I conducted with him and which is printed below. Most of the poems discussed in the interview appeared in Roi's Whether or Not (Raka Publications, 2000).

Roi Kwabena's Whether or Not is an important collection of poems by a writer who is really committed to the word in performance and to his place of birth. Roi's commitment to the oral tradition appears in the poem entitled "New Age Bois Warrior" with the powerful Chalkdust quote "to hell with de law, ah declaring war". In this poem, the "bois fighters" (stick fighters), "jammettes" and "obeah doctors" all come to life in a rich tapestry of sound. Poetry as sounded word defines Kwabena's art, as shown by the lines "ah go lead de argument / like dem debating group of barrack yard an' pon rose hill". The poet invokes the "heritage" of "bongo, calenda an' cannes brûlées", thus referring to the early history of the Trinidad carnival when the songs of defiance (the "calendas" or "kalindas") were sung by gang leaders before the proper stick fight began.

In the poem entitled "Cascadura", the heritage of "steel drums", "carnival parade" and "bottle Ôn spoon" brings to mind Carinival days and the joy of release.

Poems like "westindia", "geological wonder" and "Cascadura" are proof that the poet is still committed to the Caribbean and to his birth place, Trinidad. The poem entitled "westindia", with its telling lower case, testifies to the power of NAMING in Caribbean cultures as the poet re-names the islands which were given the names of Christian saints by European colonial powers like Spain. This poem is the occasion for Kwabena to reclaim the distant Amerindian past and heritage as his own : —"look. . . , we reclaimataitijxaymaca"

In this piece, the poet assumes a priest-like, a shaman-like function and reclaims his land and heritage:

"ayay

The Amerindian place-names and other cultural/historical refrences are conveniently explained in a glossary at the back of the book, which shows that Kwabena is also an educator, a teacher.

Roi Kwabena's poetry also shows his pan-Caribbean consciousness, as is shown by the poems "email" and "keep hope alive", about the eruption of the Soufrière volcano on Monserrat in 1995. The poet is thus fully aware of events taking place in the wider Caribbean (as is shown by the poem "Hang Man" with its lines about the state of prisons in "trinidad, barbados, jamaica or grenada"), but he also assesses the current situation in his native Trinidad in "whether or not". This poem contains the haunting refrain "we still thinkin' about yuh" and alludes to racial tension and the wave of crime which seems to have engulfed the island. These problems are also hinted at in "Cascadura" with its line about "muslim brothers guarding their border". Nevertheless, the poet remains optimistic and convinced that racial harmony and social peace will come eventually.

Lastly, the poet is also aware of North/South inequalities and contrasts. Indeed, the poems entitled "Forgive us our debts" and "Apparitions" are two moving pieces about the plight of the so-called Third World. The link between past exploitation and present poverty is painfully made explicit in these lines :

-"the genocide. . . the chattel slavery. . . . the indentureship. . . .the religious conversion . . . the plunder of our antiquities . . . the economic deprivation. . . .the scientific exclusion. . . ./could we expect /our debts to be forgiven/so that we may feed our people".

Thus, Roi Kwabena's poetry is thoroughly Caribbean and universal at the same time as it addresses concerns which are specific to the West Indies but also branches out into many other areas. Professor Stewart Borwn of the University of Birmingham, UK, wrote that for Roi Kwabena, the poem seems to be "an agent of dialogue" which is supposed to encourage his readers to "debate among themselves". Roi's poetry certainly achieves that aim, but it also makes readers aware of the beauty and power of the Caribbean oral tradition and of Caribbean/Trinidadian English.

2. Interview

Eric Doumerc: Could you first tell me about your background ? I understand you were born in Trinidad.

Roi Kwabena: I was born on the 23rd July 1956 in Port of Spain, on the Caribbean island of Trinidad, which was then governed as a British colony along with the sister island of Tobago. My father then an automobile mechanic from San Fernando in the south, while my mother was born in Port of Spain, capital and north of the island.

E D: What was life in Trinidad like at that time ?

R K: Life for me as a child was eventful and fascinating to say the least. Trinidad & Tobago as a result of many social experiments was multiracial. There are Africans, East Indians, Chinese, local whites, Syrians Lebanese, and various multicultural communities. The social mood at the time was one of optimism, eleven years after World War II — also the period of mass migration to Britain — the mother country (paved with gold) to rebuild after the war in exchange for perceived opportunities; with a popular local political party formed for the intention to rid us of colonialism and imperialism. The leader was Dr Eric Williams (that renowned historian, author of Capitalism & Slavery) who is also credited with the banning of his own published works locally. Eventually years later, Trinidad and Tobago gained independence in 1962, months after Jamaica over the slain corpse of a planned West Indian Federation. Williams' famous message as Prime Minister (or rather as the great prophet promised by our local clairvoyants to arrive from the sky albeit on BOAC ), "Massa Day Done!", remains an inspiration. He led a march in the rain attended by myself as a baby with my parents to reclaim the western Chaguaramas peninsular where the US (as in Cuba) maintained a Naval base. This occupation was made possible through the Bon Accord treaty with Britain. Later in a famed public square (Woodford Square which Williams renamed as the University for the People), he gave another very influential speech to the youth of Trinidad and Tobago; he suggested that the future of our country was in our school bags.

I was educated entirely in Trinidad, from prep school to university, and the most memorable years for me began in 1965 as unpopular legislation was passed resulting in labour unrest. Hordes of disaffected adults deemed criminals roved in gangs attacking communities, with their villages as protected turfs and also leading steelband orchestras that would clash stunningly on the streets during Carnival. Unemployment was rising locally. Hindus and other Indian sugar workers were organising themselves religiously and politically as a labour movement in the aftermath of an American Civil Rights Movement, KKK picnic lynchings, Anti-War demonstrations, the assassinations of Malcolm X, JFK, Martin Luther King.

Racism was effectively maintained in all sectors of my islands, blatant even in the Roman Catholic church I attended, where the descendants of the plantocracy were allowed to occupy all the front seats of the congregation. It was in secondary school, soon after the eventual Black Power uprisings (1970) that I was totally moved by the continuing social malaise. There was an armed struggle against Williams carried on by the NUFF (the National Union of Freedom Fighters) comprising various youths (four and seven years my elder). Though brilliant graduates, many were murdered by state forces as the media immortalised them as bandits. A historic tragedy, as Trinidad and Tobago to this day, has not honoured their noble intentions.

R K: I was an avid reader from three, as encouraged by my parents. My favourites were the comic books on the bookshelf. Published as the Golden Key series, with issues dedicated to classics as Prince and the Pauper, Macbeth, Joan of Arc, A Tale of Two Cities , etc. I must admit these were very influential on my earliest outlook. There were also the regular callers to the door, the Jehovah witnesses with their intriguing magazines Watch Tower and Awake which I also perused. At primary school, I was also forced to study the classic English poets. Poetry three and four pages in length that a child at seven or ten had to commit to memory, understand and recite with demeanour. I have some uneasy memories of my colleagues being physically abused with freshly cut guava and tamarind whips by teachers who themselves were denied experience of life on "Blighty", never to see the chalk hills at Dover, the Sands-o-Dee on the west coast, near Liverpool nor Wales. These teachers never experienced the cold of winter, but were able to aptly describe to their classes falling fog and mist as we sweltered in the blazing sunshine.

The public controversy at the time was validity of colloquial speech versus spoken Standard English. My age group were the ones caught between, discriminated by class religion, class, religion, surname and worst of all skin complexion. There was a failing of a Concordance between denominational schools and the proposed future for the national education system by Williams' nationalist Government. I was very moved by the contradictions in the church; the European statues (which were painted black in protest by Black Power demonstrators who invaded the Catholic cathedral in 1970) perplexed me. I was confused by the teaching of a Biblical commandment against idolatry. Then, through perhaps divine providence, a new text was introduced at primary level titled The Sun's Eye, edited and complied by Andrew Salkley and Anne Walmsley. This was the unexpected miracle that laid bare our aspirations as mirrored by the poets Martin Carter, Derek Walcott, writers Timothy Calender and Barnabas Ramfortune among others. This was a new chapter in our understanding of literature, as these were our writers speaking to us in a language we could comprehend. Poems like "Song of the Banana man", "Always remembering the Sea" or stories such as "The Honest Thief" and "Stone Soup" are etched in our hearts.

In 1971, I composed my first poem, entitled "Why Black Power" which was published in the Liberation broadsheet of the Black Power movement. I also performed that poem at a regional rally to rapturous applause, being just 14 years of age. My first collection Lament of the Soul appeared in 1974 and was launched at my parents' home with a gathering of several local poets. It was at this event that I decided to launch a writers' collective, Afroets Press, to empower aspiring, young and unrecognised writers. From thence, numerous poetry readings were staged for over succeeding decades at unusual venues such as progressive trade-union offices, city halls, groceries, parish halls, and even a bank.

E D: Judging from the poems collected in Whether Or Not, your poetry bears the imprint of the Caribbean oral tradition? Do you see yourself primarily as a performer or simply as a poet?

R K: Both, as accepted over those trying years. I have had to consciously adopt the manner of Anansi the spider or better still a (twenty-four hour) chameleon. As it was difficult to earn a living as a writer/artist, far less a poet, I became an advocate for copyright laws, and the struggle for equality, a recorder of the wrongs to be put right, a defender of an endangered maligned culture with declining social values in the face of a vigorously promoted cultural imperialism. These were the years of political fallout, the introduction of security guards, burglar alarms, violent labour unrest, detention of free thinkers, the oil boom closely followed by a recession. During the period 1975-1980, Afroets published over fifty-five writers and promoted twenty artists. I was forced to resort to soliciting advertising from the perpetrators of the same ruthless cultural onslaught, in order to survive as a publisher, with a measure of some success, publishing magazines, postcards, pamphlets, journals on natural health, drug abuse, art, history, labour history, children stories, women's struggle, literature, producing/promoting lectures, concerts that included choirs, dance performances, political comedy, art and craft exhibitions. I became a cultural activist.

E D: Do you perform your poetry to a musical accompaniment ( drums, tapes, etc) ?

R K: Yes I perform with my drum and own voice. In the past, I have worked with background vocals provided by vocalists and choirs. But special emphasis is always placed on audience participation, keeping alive the ancient tradition of the griots based on call and response. My CD Y42K is evidence of that practice.

E D: Do you see your poetry as a form of "public art", that is an artform rooted in a specific culture and community ?

R K: My work is public on and off the page. I do not believe that the spoken word is any more valid than the text on the page. My influences are varied, owing to the principle of the acceptance of all cultural expressions.

E D: Moving to some of the poems collected in Whether Or Not. Naming obviously looms large in your poetry ; for instance the poem entitled "westindia" is primarily concerned with this issue. Could you tell what drove you to write this poem ?

R K: "westindia" was composed specifically to address the maintained error of Columbus that we are Indians of the west. Research showed me this error was north in origin as those explorers as some academics today still refer to ancient Africa and Asia under the erroneous category: Oriental. Self-realisation taught me that we should seek justice for our forebearers. My mother is descended from those ancient peoples who were not cannibals. The indigenous peoples of the west have given us so much and yet we are still taught that their existence remains irrelevant. For instance we owe to them, the likes of potato, pineapple, banana, cocoa, cassava, maize, cotton, tomato, tobacco and asphalt. Words of their lingua have been adopted by the modern world, for instance "hurricane", "cayman" "manatee" and "hammock".

Naming remains of import as sound is vibration. There remain many sacred places in the Caribbean bearing original names. In the poem, I evoke not only the deities, but original island names renamed by the colonials. It is a small part of giving due where it is due, so that educators would stop teaching our children that they were cannibals and instead identify them by their original names: "taino", "gallabi", "karifuna".

E D: The Amerindian presence is another major influence in your work. Indeed your poems are peppered with Amerindian names. When did you first become interested in the Amerindian heritage in the Caribbean? Is this linked with your Trinidadian background (I'm thinking of the Santa Rosa madonna in Arima . . . ) ?

R K: As a child with my parents we often visited the local museum. There I was often moved by the little attention paid to the artefacts of the indigenous people as opposed to the retrieved old cannons of the colonial forts. My sojourns in various isles of the Caribbean reinforced the need to instil more pride among our people, banishing the myths of a misunderstood past. The violent resistance (in my opinion justified) by original inhabitants to the treasure-hunting arrivants in the 15th century (privateers, pirates, slave traders, religious zealots, explorers) illustrated the desperation of a cornered civilisation. These fair emerald isles were bathed in the blood of innocents more so than perhaps what occurred in Europe during the Inquisition. I remain fascinated by the architecture and use of living spaces, the caves, structures like pyramids, tapia, ajoupa and the tasty foods that still tempt the palate five centuries later, for example the pone ( a cake), the cassava bread/ paymee (baked in banana leaves), the arepa (spiced pie), the roucou (a flower used as colouring in food and also used for protection from sunburn), also not excluding the Jamaican bamee.

Santa Rosa is but a vestige of the colonial and religious Spanish zeal diluted with indigenous, African and Asian traditions. The Spanish gave up Trinidad to the English without a battle, being unable to defeat the Ineri (the original inhabitants). But continuing in another vein, permit me to interject that your and my history is so inter-linked that there is obviously no way we can undo those ties. For instance, after the French revolution, a lot of French planters fleeing Haiti (then renamed Santo Domingo) were allowed to settle in many islands under control of the British. This was called the Cedula of Population, circa 1738. This is the plan that allowed the cousin of Marie Antoinette (a ruthless planter named Count Beggorat) and many others to bring their slaves, their language, culture, and their Catholic religion and despicable attitude toward blacks and to settle in my village, Diego Martin, in and other lush parts of Trinidad, under Spanish law but governed by the British. This is an example of the united Europeanisation of the region.

E D: Other poems deal with more current problems like third-world countries' international debt ("Forgive Us Our Debts") or the setting up of a Caribbean Court of Justice ("Courting New Appeals"). Do you see yourself as a kind of griot/journalist or some kind of newscaster?

R K: "Forgive us our debts" and "Courting new Appeals" simply seek to mirror the aspirations of ordinary people. The artist has a responsibility to become part of the vanguard of the ongoing struggle for liberty, dignity, equality and justice. I accepted this role consciously from age 18, being moved by the examples of (now ancestors) teachers such as Curtis Mayfield, Sun-Ra., Mahalia Jackson, Paul Robeson, Aimé Césaire, Franz Fanon, Nina Simone, Jimmy Cliff, Andre Tanker, Fela Kuti and countless others. My path was further confirmed by way of personal advice from CLR James, that veteran thinker, in 1980.

E D: The poem entitled "Cascadura" is very moving and full of nostalgia, but also alludes to ethnic tension in Trinidad ("muslim brothers guarding their border"). What was your main inspiration for this poem ?

R K: The main inspiration for "Cascadura" is nostalgic, yet it is a conscious attempt to celebrate cultural life in Trinidad, and yes, mention is honestly made of the misunderstood existing tensions. Your quoted line also alludes to the reality that African-Trinidadians have unashamedly re-embraced one of the religious tenets of their forebearers of Dafur, Mali, Songhai, and other great African Islamic empires. Of this I am particularly pleased as many Mandingo slaves brought to my island were denied practising their way of life. This fact was erased from our history by the ones who sought to convert my ancestors.

E D: The poem entitled "New Age Bois Fighter" begins with a quote from a song by the Mighty Chalkdust and invokes "de spirits ah all dem bois fighters". Are stick-fighting and calypso main inspirations for you. Do you draw strength from this heritage ?

R K: Chalkdust (Dr Hollis Liverpool) remains one of my favourite calypsonians (among the late Lord Kitchener, Ras Shorty, Merchant and yet still with us the Valentino, Black Stalin, Blakie and others). Chalkie remains a friend as well as an early reader, having purchased many of my now out-of-print titles for his library. However, it was the now deceased anthropologist Dr J.D. Elder who first made me aware of the originality of Kalenda (stick fighting), Bongo, Carnival & Kaiso. Further reading led me to the works of also deceased anthropologists Andrew Carr and Andrew Pearce, who were among the first to conduct vital field research on these traditions.

Our children need to be told of the efforts of those chanting stick-fighters, drummers (the drum is still banned by archaic European laws retained in the so-called colonies to this day), even those women whose heroic organising planted the seeds for the trade-union movements, tamboo-bamboo players whose inventiveness led to the steel pan (the greatest musical invention for the 21st Century), played all over the world yet to be included on my country's education curriculum), forgotten reformers who bled for a nationalism which is forsaken today.

From a musical point of view, our Kaiso has grown and gave birth to calypso, soca ragga, and chutney (the latter with the influence of Asians). But sensible lyrics have been banished. Even double-entendre, humour and messages have disappeared, so that today only synthesisers, electronically programmed rhythms, gyrating waists and waving a sweat-soaked rag are in vogue (very much reminiscent of the old days when the French bourgeois waved their handkerchiefs in such like processions. So yes, these aspects of my culture do give me energy to continue writing.

E D: The poem entitled "Whether Or Not" refers to the current situation in Trinidad, with the political instability, the racial and ethnic tension, the economic problems, etc. Is the refrain "we still thinkin' about youÉ" addressed to the family and friends you left behind ? To me, it seems like a very compassionate poem.

RK: It's all that and more. The refrain also refers to the many youngsters who have disappeared over the years in Trinidad without a trace. Yes, there are references and predictions as well.

As you may or not be aware, kidnapping, murders and crime in general have assumed crisis proportions without a clear resolution in sight. Poverty is the parent of crime, and unless we empower the needy, we will reap more woe as time passes.

I feel real anxious as politricksters are playing their usual game and an unscrupulous few profit from this scenario. The newspapers headlines scream anguish and exhibit images of grief-stricken relatives hovering over newly prepared graves or decomposed corpses. Moreover, the recently exposed corruption borders on disbelief. I am stunned to say the least by the recent revelations as immaculate British lawyers are hired to repatriate the loot.

E D: There are also two pieces about the eruption of the volcano in Montserrat ("email" and "keep hope alive"). Could you tell me more about these two poems?

R K: The first cited was in response to an email I received from an educationist then reading for a PhD who shared her feelings about Heroes' Day celebration in Montserrat and its significance as that island was the first to have slave uprisings. "Keep Hope Alive" was commissioned by Kamara Video Productions of Birmingham, UK who were funded by a millennium grant to assist the smooth settling of newly arrived young islanders fleeing the volcanic eruption on Montserrat. Actually, it is also available in video format featuring a young woman from the island reciting the poem with musical accompaniment provided by Ras Asha of Psalms 77 Production and drumology by yours truly. That project further convinced me of the validity of my creative and literary journey.

E D: Anything you would like to add?

R K: Well, thanks for this interview, a rare and treasured opportunity. I am pleased with recent developments as regards reparations for human right violations internationally (including chattel slavery). Amnesty International's scathing report on prisons in Trinidad and ample condemnation by same of the precarious situation facing T&T citizens validates my speeches as a senator and my last two collections of poetry. Amnesty International's continued opposition to capital punishment and human rights abuses is reassuring.

I would also like to acknowledge all my readers and supporters over the years in the Caribbean, Africa, Europe, the Americas and most recently Japan. As you are aware, since becoming Poet Laureate (2001-2002) of Birmingham, UK, I have also been actively involved in historic research into the indigenous peoples of the Americas and their links with the Muurs who significantly contributed to European civilisation over the centuries. There is no clash of civilisations. Post-modernism is an attempt to hoodwink southerners into thinking we participated in a modern world.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home